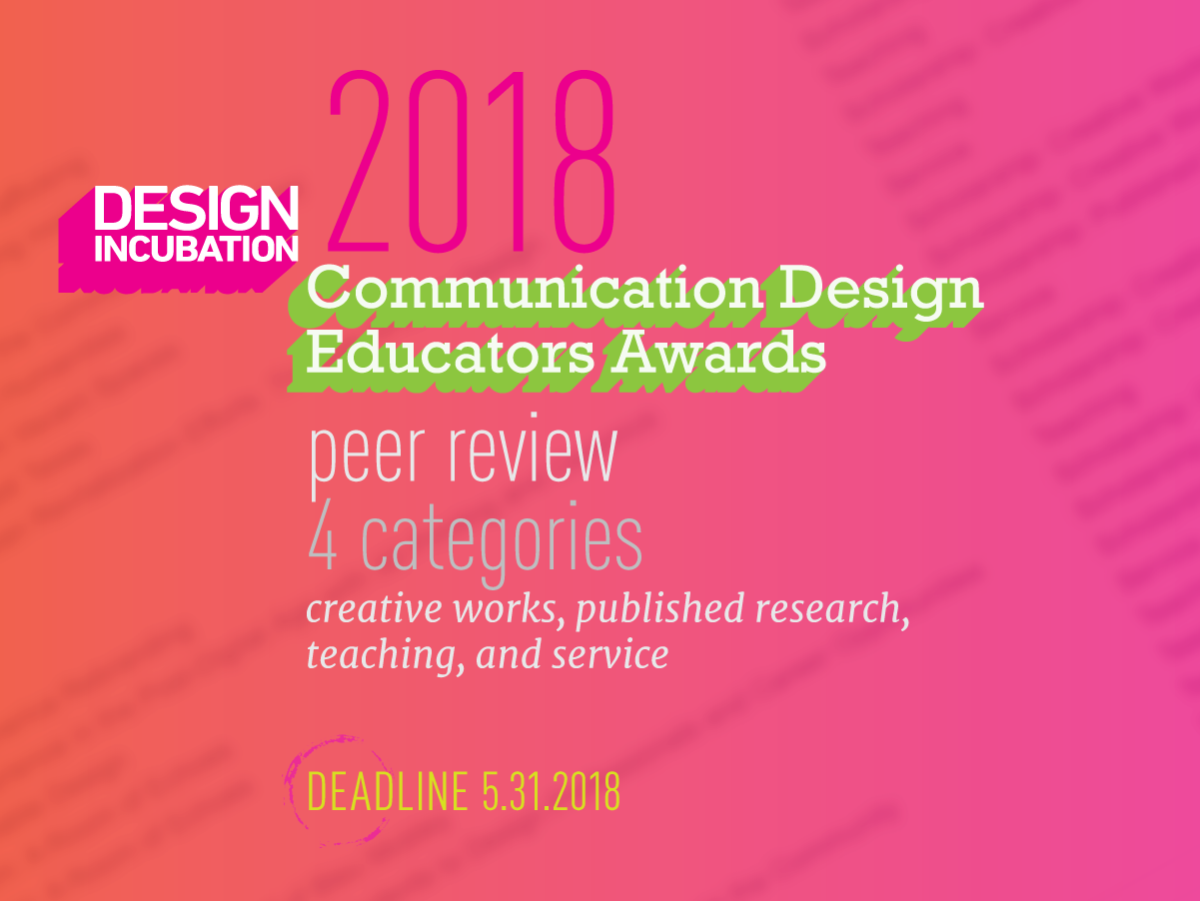

2018 Design Incubation Educators Awards competition in 4 categories— Creative Work, Published Research, Teaching, Service.

Call for Entries: Deadline, May 31, 2018

CATEGORY: SCHOLARSHIP CREATIVE WORK

Scholarship: Creative Work Award Winner

George Garrastegui

Assistant Professor

Communication Design

New York City College of Technology, CUNY

Scholarship: Creative Work Award Runner Up

Susan Verba

Professor

University of California, Davis

CATEGORY: SCHOLARSHIP PUBLISHED RESEARCH

Unawarded

CATEGORY: TEACHING

Teaching Award Winner

Helen Armstrong

Associate Professor

North Carolina State University

CATEGORY: SERVICE

Service Award Winner

Mariana Amatullo

Associate Professor

Parsons School of Design, The New School

Andrew Shea

Assistant Professor

Parsons School of Design, The New School

Jennifer May

Director, Designmatters

ArtCenter College of Design

Recognition of excellence through peer review in scholarship, teaching, and service is fundamental to the professional development of communication design academics. To support this need, Design Incubation established the Communication Design Educators Awards in 2016.

An independent jury of esteemed design educators is invited by the Awards Jury Chair. This year’s jury chair, Maria Rogal, invited these internationally recognized jurors: Jorge Meza Aguilar, Ruki Ravikumar, Wendy Siuyi Wong, and Steven McCarthy. Rogal writes, “this jury reflects the diverse perspectives and experiences that exist in communication design today.”

The awards acknowledge faculty accomplishments in the areas of published research, creative work, teaching, and service. The award processes and procedures are rigorous, transparent, and objective. They reflect Design Incubation’s mission to foster professional development and discourse within the design community.

This year, award entries are open February 1, 2018 – May 31, 2018 via the online application. An overview of the awards program is on our website.

We are excited to announce Bloomsbury Publishing is sponsoring this year’s awards.

We are excited to announce Bloomsbury Publishing is sponsoring this year’s awards.

The 2018 Jury

Steven McCarthy is Professor of Graphic Design at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis/St. Paul. He conceived of the Design Incubation Communication Design Educators Awards and chaired the jury in both 2016 and 2017. McCarthy’s teaching, scholarship, and contributions to the discipline include lectures, exhibitions, publications, and grant-funded research on a global scale. His creative work was featured in 125+ exhibitions and he is the author of The Designer As… Author, Producer, Activist, Entrepreneur, Curator and Collaborator: New Models for Communicating (BIS, Amsterdam). From 2014–2017, McCarthy served on the board of directors of the Minnesota Center for Book Arts.

Jorge Meza Aguilar is Professor of Strategic Design and Provost for Outreach and Collaboration at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City, where he founded the Bachelor in Interactive Design and the Master in Strategic Design and Innovation programs. He is widely recognized as an expert in strategic design and is the founding Director of Estrategas Digitales which focuses on research, strategic design, branding, trend forecasting, branding, Internet, and digital media. Meza is also a consultant and entreprenuer and holds degrees in art, graphic design, and systems engineering. Previously, he studied in and worked as a designer in Poland at Advertising Agency Schulz.

Ruki Ravikumar is Director of Education at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, a position she has held since April 2017. She joined the museum following thirteen years of service at the University of Central Oklahoma, where she held successive positions as professor of graphic design; director of graduate programs; chair of the Department of Design; assistant dean; and most recently, as associate dean of the College of Fine Arts & Design. In addition to her practice as an educator and published researcher in the areas of intersections between graphic design and culture and their impact on design education, she is also an award winning graphic designer. Further, she has served in leadership roles at the local and national levels of AIGA, the professional association for design.

Maria Rogal, Jury Chair, is Professor of Graphic Design, School of Art + Art History at the University of Florida and was Interim Director from 2015–2017. She is the founder of Design for Development (D4D), an award-winning initiative to co-design with indigenous entrepreneurs and subject matter experts to generate sustainable and responsible local outcomes. She has lectured and published about D4D, recently co-authoring “CoDesigning for Development,” which appears in The Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Design. Her research has been funded by AIGA, Sappi, and Fulbright programs, among others, and her creative design work has been featured in national and international juried exhibitions.

Wendy Siuyi Wong is Professor and Graduate Program Director in the Department of Design at the York University, Toronto, Canada. She has established an international reputation as an expert in Chinese graphic design history and Chinese comic art history. She is the author of Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua, published by Princeton Architectural Press (2002). She is a contributor to the Phaidon Archive of Graphic Design (2012), The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design (2015), and acts as a regional editor of the Greater China region for the Encyclopedia of East Asian Design to be published by Bloomsbury Publishing. Also, Dr. Wong has served as an editorial board member of Journal of Design History.

Like this:

Like Loading...

We are excited to announce Bloomsbury Publishing is sponsoring this year’s awards.

We are excited to announce Bloomsbury Publishing is sponsoring this year’s awards.