Shreyas R Krishnan

Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts

Washington University in St.Louis

The mutilation of Surpanakha is a well known plot point in the Hindu epic Ramayana. Cast as a demoness and the female abject in this narrative, Surpanakha serves as a crucial turning point in the larger epic. When her nose and ears are cut off as punishment for perceived sexual transgressions, it sets in motion a chain of events that form the remainder of the Ramayana’s storyline.

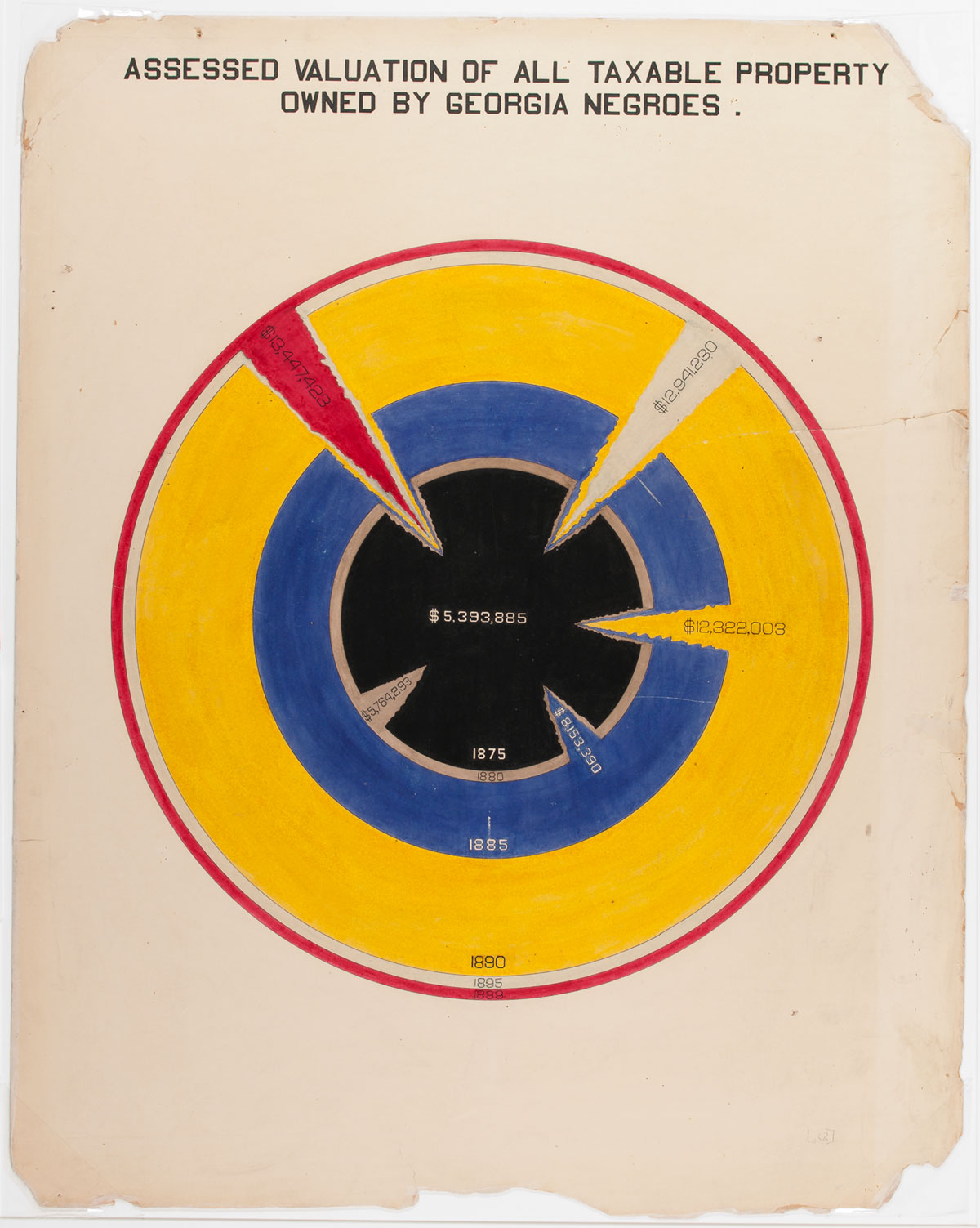

This paper examines visuals of this particular scene as illustrated in comics on the Ramayana story published by Amar Chitra Katha. This examination references existing research on the history of Amar Chitra Katha comics and their representation of women characters, while additionally applying the lenses of gender and film theory in its approach. Three issues of Amar Chitra Katha are first compared for their illustrations and narration of this moment of violence, before moving on to juxtapositions with the same scene in other contemporary long-form illustrated Ramayanas, and with photographer Jodi Bieber’s Time magazine cover image of Aisha Bibi who was similarly mutilated by the Taliban.

By analogizing these visuals of gendered violence, and interrogating the relationship between text and image in each of them, this paper analyzes how Surpanakha’s mutilation is illustrated for public consumption.

This research was presented at the Design Incubation Colloquium 7.3: Florida Atlantic University on Saturday, April 10, 2021.