Vida Sacic

Associate Professor

Northeastern Illinois University

Visual communication skills provide a backbone for participation in a shared cultural exchange. Yet, universities often fail to offer tangible ways to foster long term accessibility and inclusion.

Northeastern Illinois University is among the nation’s leaders at graduating students with the least debt while serving the most diverse group of students in the Midwest.*

In the span of last eight years, we have formed a program in Graphic Design tailored to students who come from racially, ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse families and communities of lower socioeconomic status.**

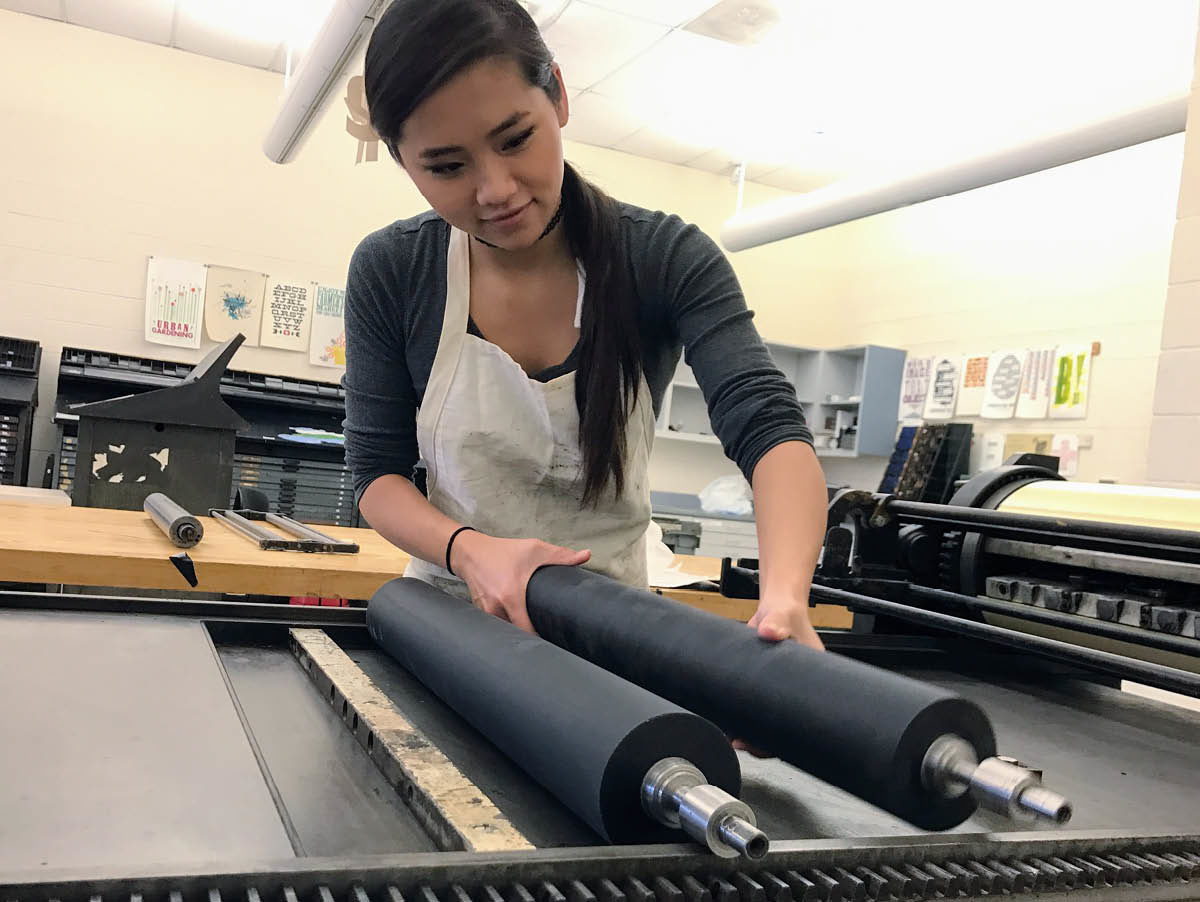

Students often define success as the ability to use design skills to earn a living following graduation. Self-expression builds our students’ confidence and assertiveness as designers. For this reason, storytelling organically became a focus of the program. As it became evident that diverse students achieve most favorable learning outcomes in collaborative spaces where they can interact face-to-face, the heart of our program became our letterpress printing class.

Our growing letterpress type shop houses digital and analog tools. Students are required to collaborate with class members and beyond to complete projects, thereby practicing cultural sensitivity and interpersonal communication skills. The experimental nature of print and mechanics offers students an ability to slow down and consider their work more carefully, while introducing elements of chance and discovery to their process. This arrangement offers a unique environment to raise 21st century citizen designers and a valuable model for integration practices in design education. This model can be replicated in any makerspace environment that uses high tech to no tech tools.

Beneficial outcomes are evident as increasing amounts of our students are finding employment in the field, applying their skills to relevant positions and using their lived experience as a source of knowledge that can serve as an asset in their applied practice and beyond.

* data by U.S. News & World Report, September 2017

** 38% of Northeastern Illinois University students declare themselves as Hispanic/Latino, 31% Caucasian, 11% African American, 9% Asian, with the rest listed as other.

6% are identified as Non-Residents (including undocumented students).

55% of our students are non-traditional students, defined as postsecondary students who are 25 years old and older. They are contrasted with traditional students, aged 18 -22, who enroll immediately after high school, attend full-time, live on campus, and do not have major work or family responsibilities.

data by www.collegefactual.com

This research was presented at the Design Incubation Colloquium 5.1: DePaul University on October 27, 2018.

Like this:

Like Loading...