Dave Gottwald

Assistant Professor

University of Idaho

Reverse engineering has long been practiced in lab courses in computer science and high technology development. The concept is rather simple—in order to truly understand how something works, you have to take it apart and put it back together again.

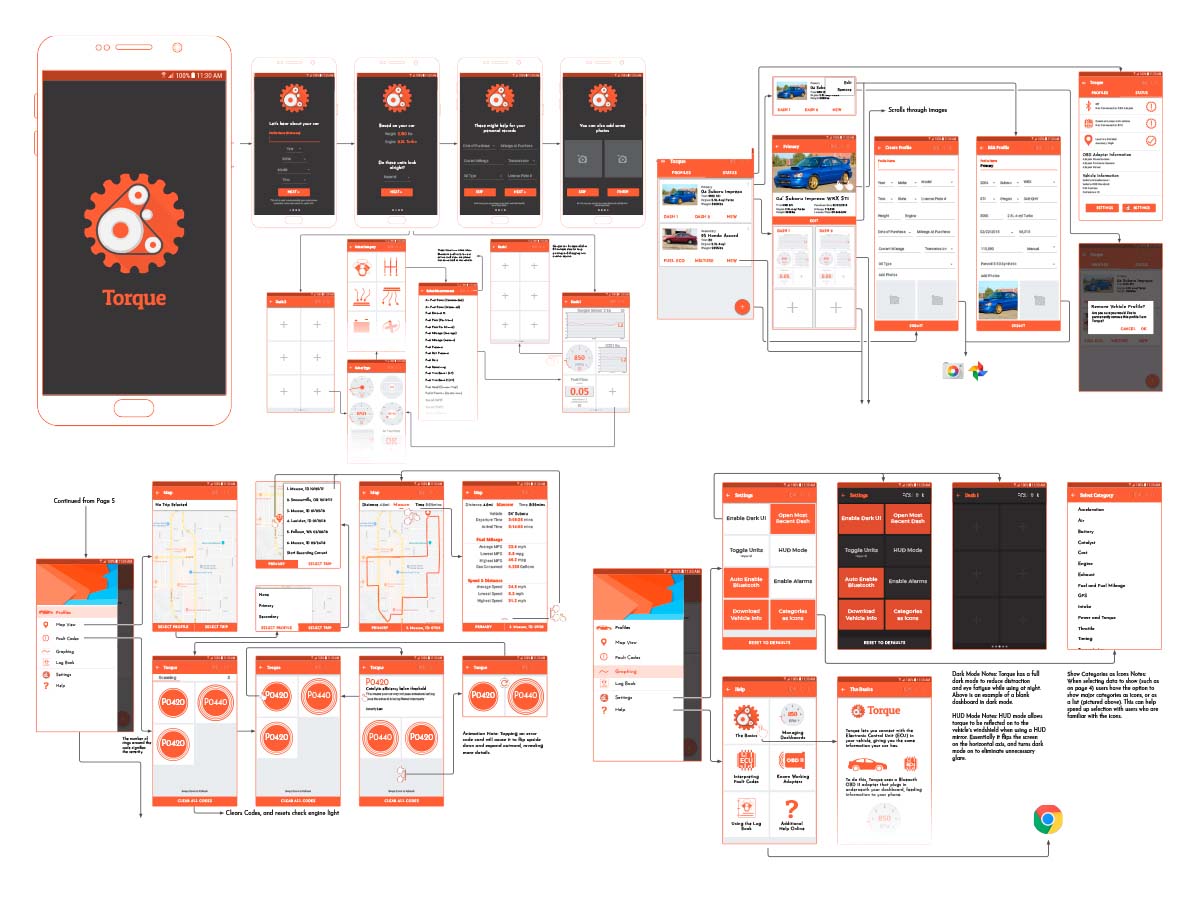

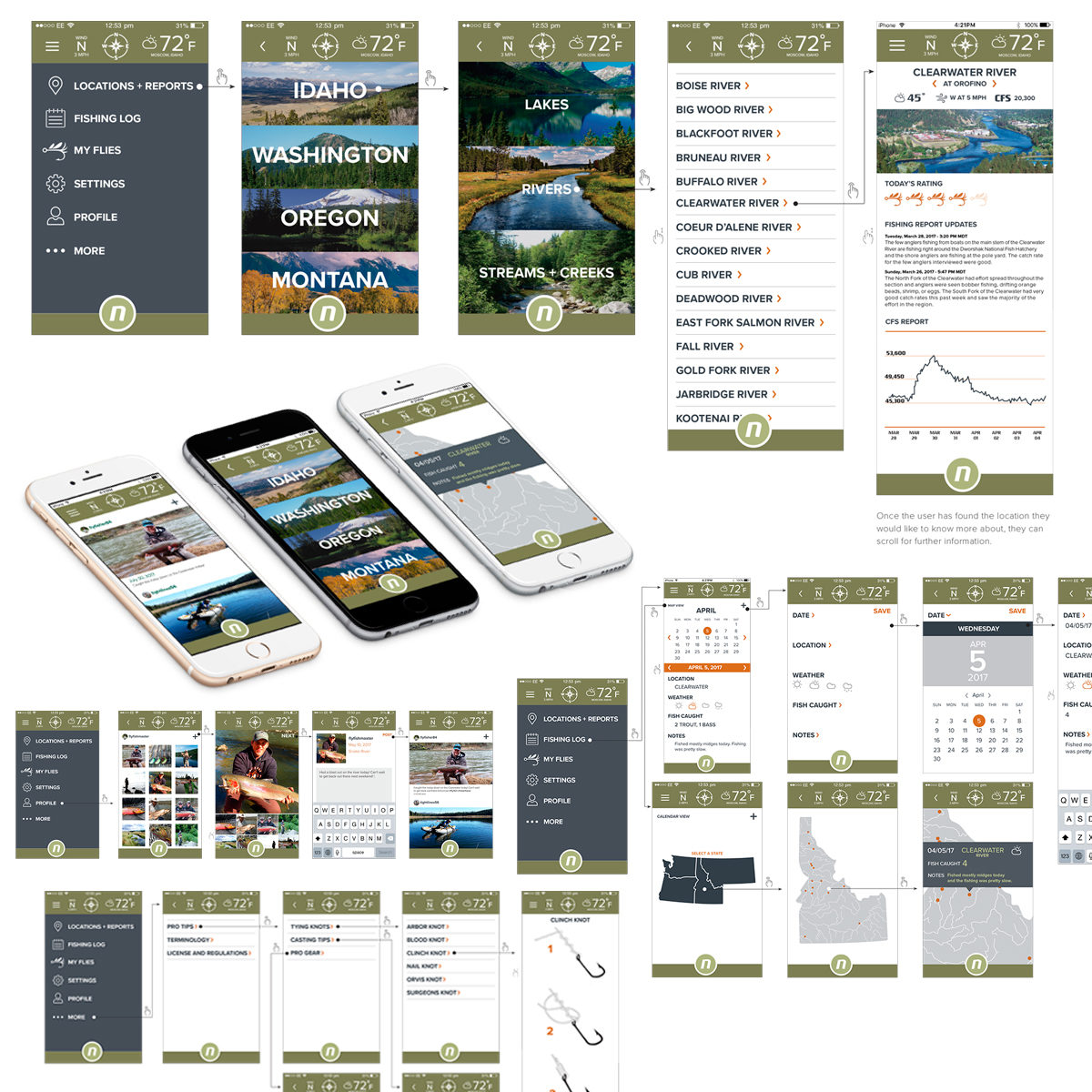

In my introductory course in UI/UX design, students are assigned three projects which mimic a reverse engineering process. For Deconstruction they choose an existing mobile app, propose a conjectured user persona based on their own use, and then document user flows of interactive functionality, using their phones to capture every screen. Organizing these screens into flows facilitates a direct approach in understanding navigation, visual hierarchy, and functionality. In this students attempt to “map” the product and speculate on why certain design directions were taken. For Reconstruction students find an app to redesign. User interface and user experience are considered equally; deficits in both aesthetics and functionality are addressed. At this stage students move beyond speculation and begin to integrate actual research into the development of their product and user personas as they design screens and document user flows.

Finally, the last half of the term is devoted to their own unique app product. Construction builds on the first two projects, yet with a more thorough research and testing phase. Students are tasked with building a live prototype designed with industry-standard software and conduct formal user testing in a group setting. Ideation and development time for this final project is noticeably accelerated, as they’ve already undergone the process twice before. Mimicking a reverse engineering process also provides a detailed structural comprehension of interaction design. By approaching apps from the inside out, students report a greater understanding of their mobile devices as designed content systems, and they are better prepared for more advanced interaction projects.

This research was presented at the Design Incubation Colloquium 6.3: Fordham University on May 16, 2020.