Monica Maccaux

Assistant Professor

Graphic Design

University of Nevada, Reno

When considering the multitudes of typeface choice on the market, how does one approach the challenge of designing a typeface that is different from the competition? With the abundance of typeface choices, why is there a need for yet another typeface to be designed? These are valid questions when approaching the creative process of typeface design. There is the potential for there to be as many typefaces as there are people in the world; meaning, the possibilities are endless in the personalities and function of typefaces, and have the potential to grow along with the population.

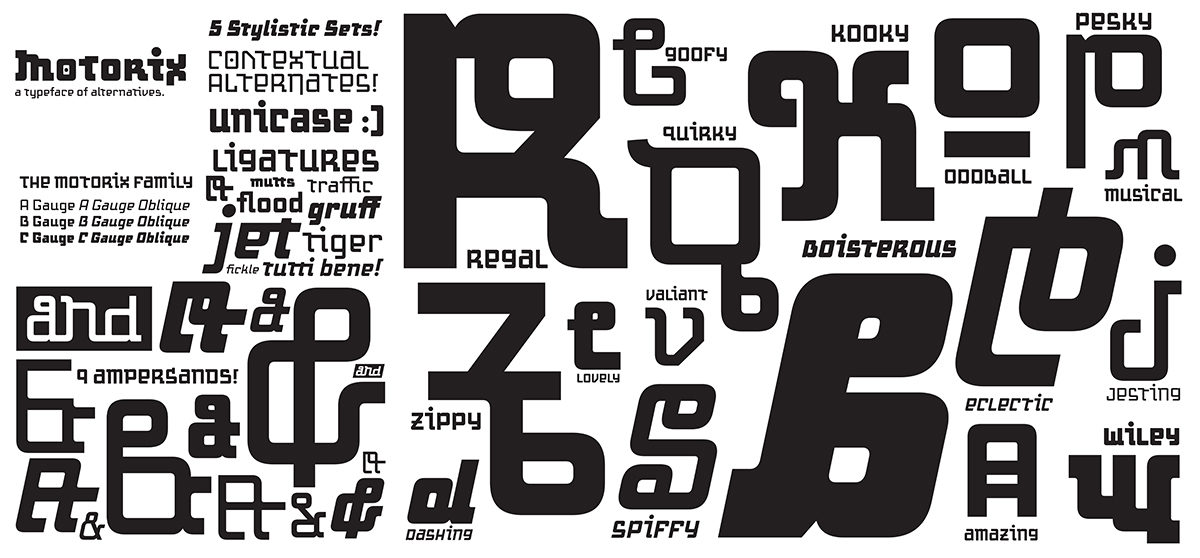

The typeface ‘Motorix’ solves the fatigue to a gluttonous font market by challenging the rules of form, beauty, and function all the while pushing the limits of what language looks like. The Latin (or Roman) alphabet, as it stands today, has undergone centuries of change and evolution which has resolved itself to current norms in letterform recognition. What will our letterforms look like in another couple of centuries? Will the letter ‘A’ still look the same? Will there be new letterforms added, or old ones removed? What can the letter ‘A’ look like? With the typeface ‘Motorix’, these questions were considered, along with how the expectation of aesthetics, and practicality drive the finished product.

Beauty and aesthetics aside, when approaching typeface design, one has to acknowledge that to design type, is to design language. As the designer of language, there are certain considerations that need to be made when formulating the letterforms: legibility, readability, beauty, form, versatility, and utility. It is no easy feat to design a typeface that is beautiful and practical, and has many applications (headlines, body copy, etc). But to design a typeface that confronts the notions of what beauty and practicality are, along with pushing the unspoken ‘rules’ of what language should look like, is something altogether different, and continues to be a modern-day challenge in typeface development.

This research was presented at the Affiliated Society Meeting: Design Incubation Special Program on Typography on February 23, 2018.