Drew Sisk

Assistant Professor

Clemson University

From early technologies in photography and film, to the emergence of the desktop computer as an accessible tool for making creative work, technological advancements have triggered simultaneous trepidation and enthusiasm among artists and designers. We see the same reactions with AI now.

AI is changing the way we approach creative processes, making them more fluid, generative, and fast-paced. More importantly, it is fundamentally altering the way we perceive images and objects of design. In the same way that Dziga Vertov’s Kino-Eye film technique in the 1920s sought to use cinematography and editing as ways to create form that is “inaccessible to the human eye,” AI will continue opening up new forms of perception that we cannot even imagine. In this presentation, I will apply the work of Dziga Vertov, Walter Benjamin, John Berger, and Hito Steyerl to the current discourse on AI and design.

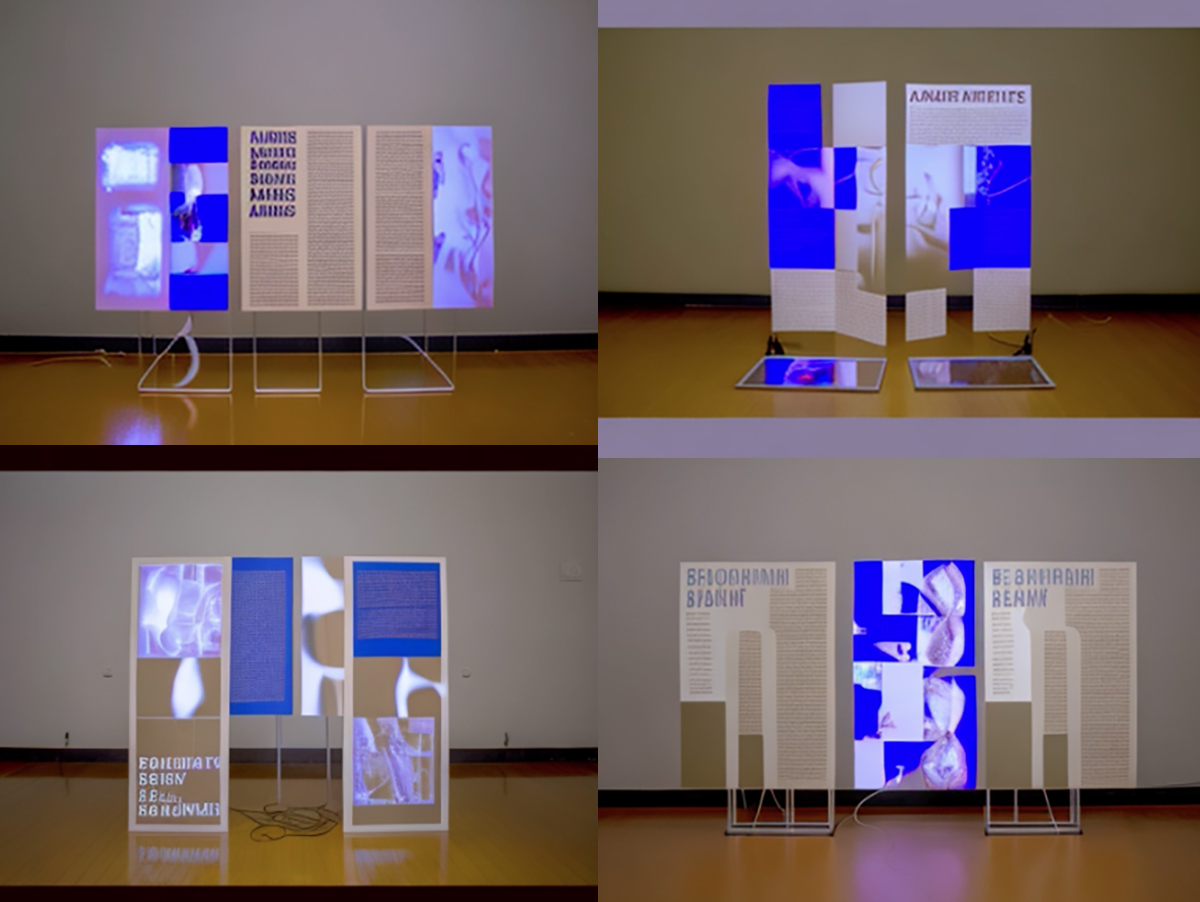

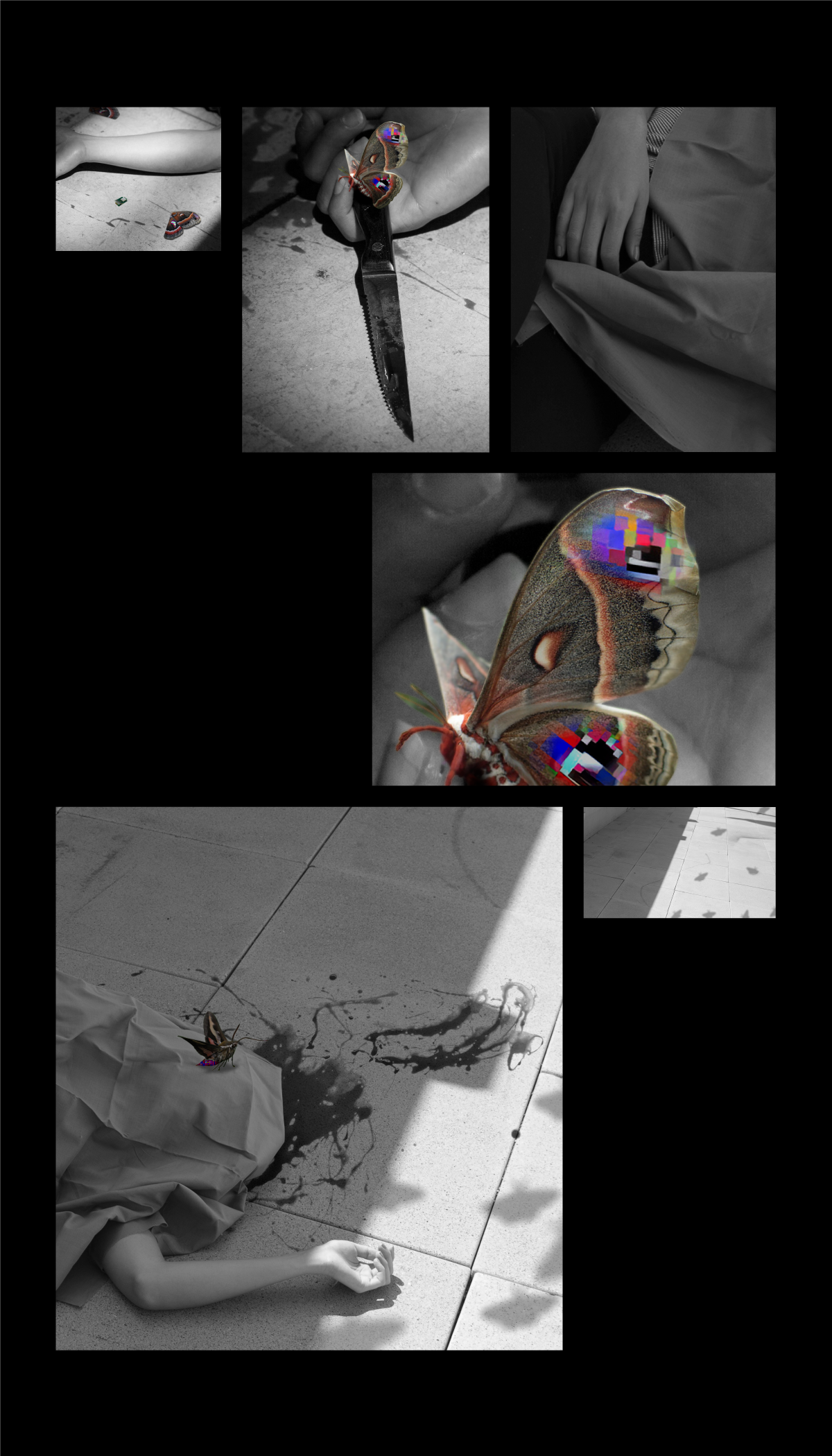

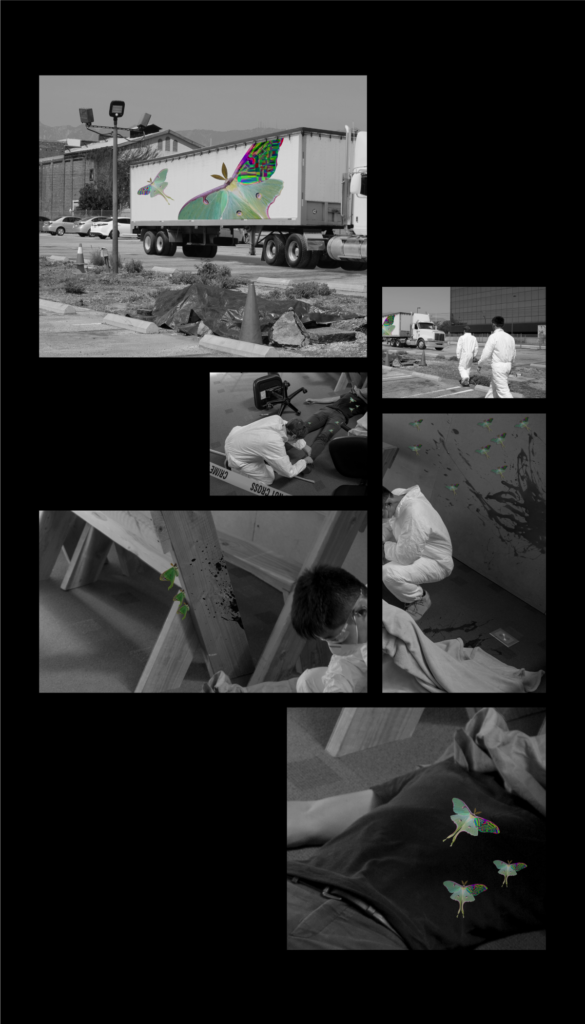

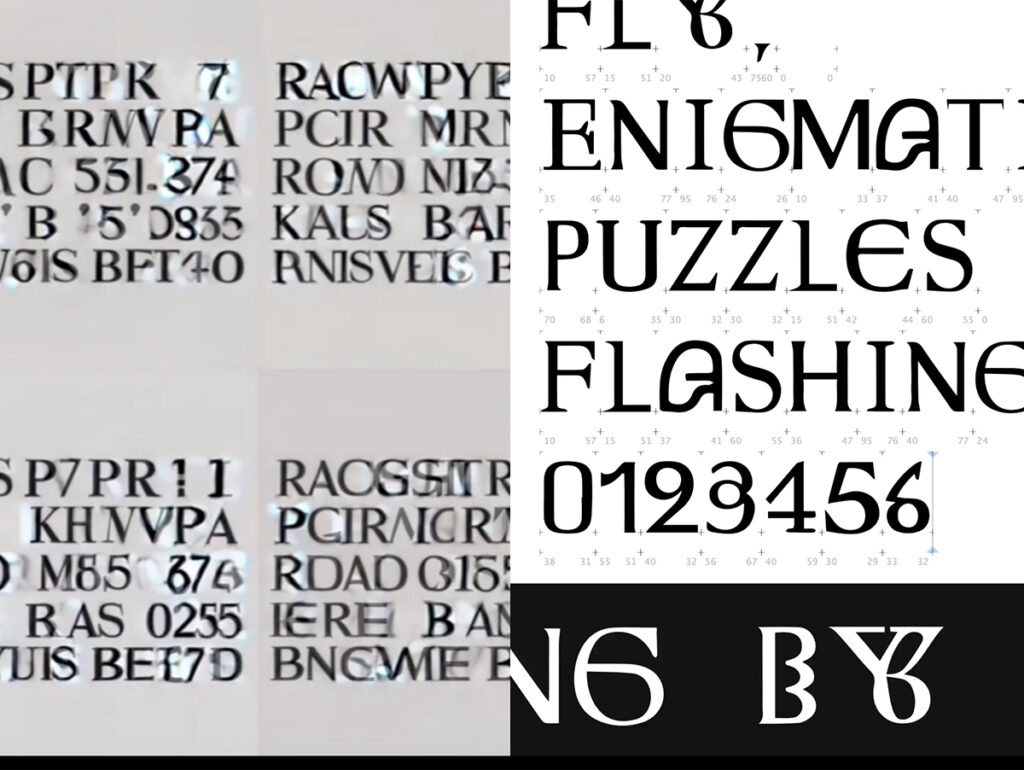

The design studio and classroom have proven to be fruitful spaces to explore AI. In this presentation, I will share some of my own nascent experiments using AI in a closed-loop approach that yields content that seems familiar and uncanny—alternate realities and speculative futures at the same time. I will also share work from my advanced graphic design students, who have been experimenting with AI tools and making speculative work that critically engages with AI. Artificial intelligence presents us with new possibilities for making form, but, more importantly, our work requires us to wrestle with the ethics and consequences of this rapidly expanding technology.

This design research is presented at Design Incubation Colloquium 10.2: Annual CAA Conference 2024 (Hybrid) on Thursday, February 15, 2024.