Sajad Amini

Assistant Professor

DePaul University

By exploring the historical roots of calligraphy and typography in one of the world’s most ancient civilizations, we can uncover the origins of some genuinely captivating scripts that still serve as powerful symbols of Arab and Persian cultures today. This narrative commences with the Islamic doctrine’s prohibition of natural imagery, prompting Iranian scholars and calligraphers like Ibn Muqla (10th century) to craft various distinctive scripts, including Naskh, Muhaqqaq, Rayhani, Thuluth, Riqa’, and Tawqi.’

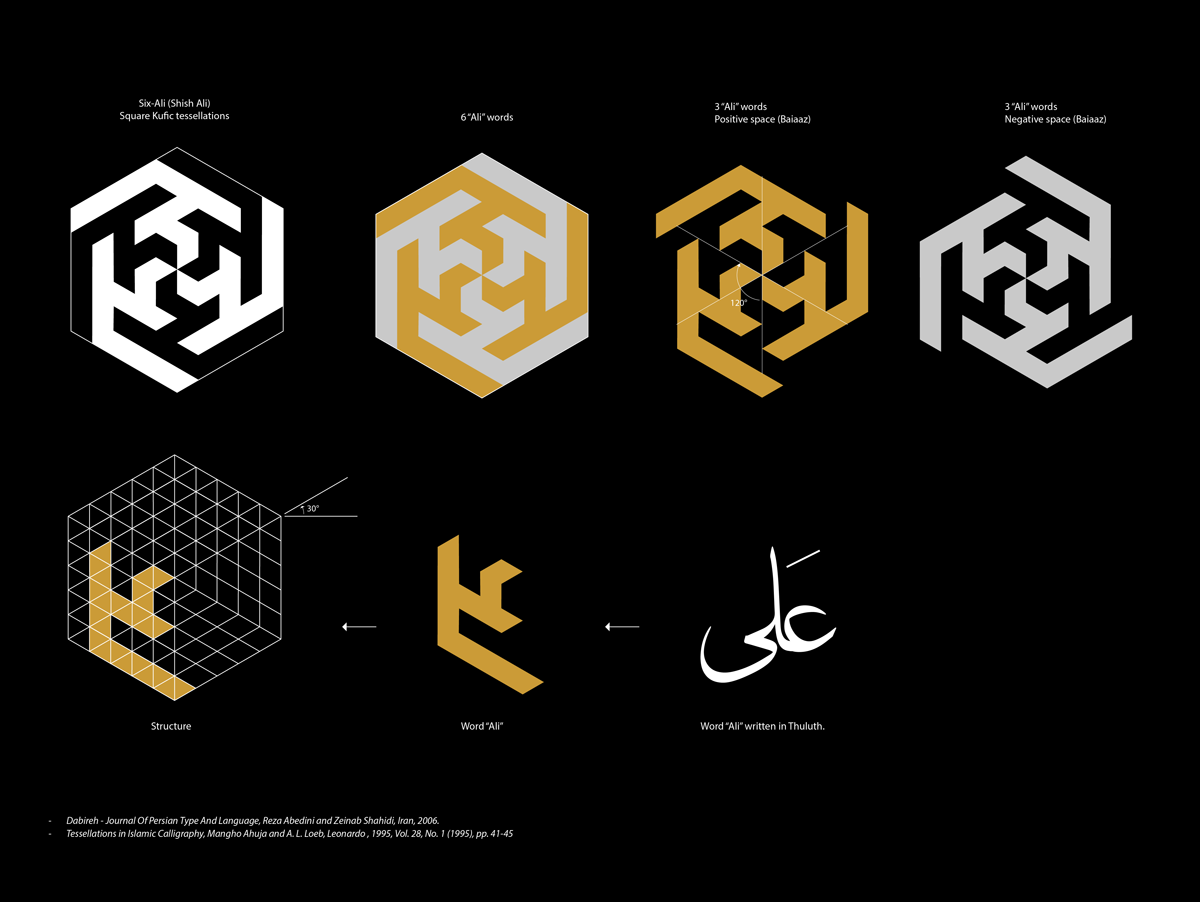

During the prosperous Islamic era, Persian architecture began to incorporate calligraphy as an ornamental element in mosque design, sparking the creation of a new script known as Banna’i Kufic (Banna in Farsi means building), often referred to as Square Kufic. This progressive typographic approach borrowed the square and solid geometric characteristics of its foundational structural components: bricks. It’s noteworthy that Square Kufic’s minimalistic design coexisted alongside complex calligraphic scripts like Thuluth. Diacritics were deliberately omitted, pushing the boundaries of typography to extremes and enabling the intricate formation of holy names and Quranic verses. Architects ingeniously intertwined two or more texts by manipulating negative and positive spaces. The fundamental structure of Square Kufic bears a striking resemblance to the inherent nature of pixels and the constraints of early computer graphic art. Banna’i Kufic’s modular design and adaptability have allowed it to endure as a versatile typographic foundation still in use today.

This presentation will provide an in-depth exploration of the historical underpinnings of the Banna’i Kufic and its structural rationale and aesthetic through the design lens.

This design research is presented at Design Incubation Colloquium 10.2: Annual CAA Conference 2024 (Hybrid) on Thursday, February 15, 2024.